Watchmaking post

Stop, watch and learn!

Par Joël A. Grandjean /TàG Press +41

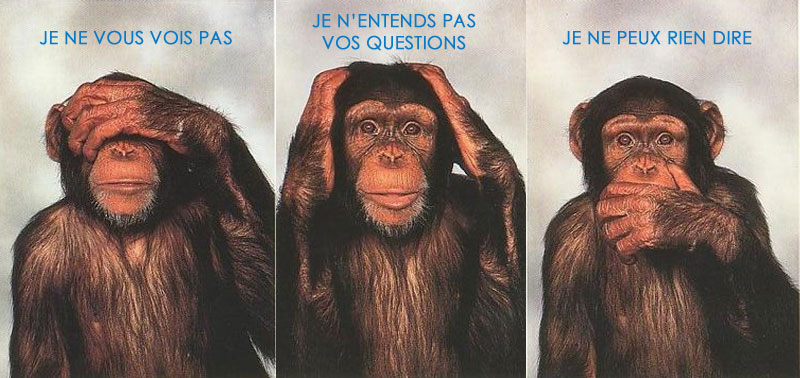

The crime of dehumanisation

Although some employees are in a position to give conferences in public halls, watchmaking companies generally take refuge in the image of the big boss, only allowing staff to speak to journalists or enthusiasts. Keeping information locked up doesn’t necessarily mean you’ve got it under control...

I have just spotted an official communiqué by the Swatch Group. It bears two clearly legible signatures, together with their telephone numbers. I’m keen to take the matter further, so I decide to write. Alas, no e-mail address… I call the switchboard, they say that they can’t divulge that information. I’m insistent, pointing out that said communiqué is available online and that the public can view it without needing to pre-register or supply a password. But it’s no good. Quietly, I fill in the contact form, I justify my request and state my occupation. Four days later, I receive an answer from the group’s spokesperson. ‘In accordance with our directives, we do not give out our employees’ e-mail addresses. However, you may use the contact form (…)’ Return to sender!

Directives from above

I admit to myself that it isn’t the employee’s fault, that all these directives come from above. So I take it to the highest level now and, as politely as I can, I make the following remarks: why do your employees display their e-mail addresses on their business cards? How is it that some of them are visible and present on Facebook or Linkedin? And sometimes, horror of horrors, even include their mobile number!

Just between you and me, with regard to the two people mentioned above, it was dead easy to reconstitute their e-mail addresses from some other examples I already had in my address book. Although just idly typing certain keywords into Google will often bring this kind of information to the surface. The Internet remembers everything and the person sought is more than likely to have belonged at one time to a work group, association or some other organisation not governed by in-house directives.

In a similar blow to my pride, and a really annoying one, I was recently denied an answer to some, perfectly harmless in my opinion, questions of a background and cultural nature. I was asking about the calibre ETA 7750. ‘Your questions touch on certain confidential, and indeed strategic, issues (…) we are therefore unfortunately not in a position to answer them. If you are seeking background information about ETA (or other of the Group’s companies), I recommend that you visit the Swatch Group website....’ I should have thought of that. There I was naively thinking that the iconic calibre belonged, to some extent, to the collective conscience, that it bore some kind of corporatist dimension that extended way beyond the interests of the company that had inherited them.

Right to quote

Need I therefore tell you about an in-depth, informal conversation I was having with a top dog in a balance-spring manufacturing firm? It was on the Friday of the famous SIHH trade fair for watchmaking suppliers and subcontractors. We were talking candidly about balance-springs and escapements... Omerta is the word that springs to mind. But get this: at his anxious request, I had to replace all the quotations I’d gleaned from my interviewee, who was a historian regarded as the living memory of the brand and official author of its publications. The fascinating interview that he had granted me, now an impersonal monologue, suddenly lost its piquancy.

Open secrets

This type of reaction isn’t just peculiar to one group. Other outfits are just as paranoid when it comes to divulging their thoughts. And that doesn’t just go for groups, but also independent, or family-run brands, where everything has to go through the boss. In the case of subcontractors, it’s understandable. They at least have the excuse of being compelled, sometimes even contractually, to respect a maximum amount of discretion. The survival of their business depends upon it.

Systematically keeping people quiet only arouses interest, and makes the interlocutor all the more curious as to the possible existence of a secret whose discovery then becomes a challenge. It leaves the door wide open for interpretation and widely-held assumptions and encourages the use of falsities to get at the truth. It paves the way for rumours, ‘open’ secrets that gravitate towards the end client, extending beyond the insider’s perimeter.

But the watchmaking product is packed with emotion and human feelings. Those feelings add an immaterial dimension likely to be enriched by anecdotes overheard on occasion, or picked up from forums or discussions. And as we’re dealing with the emotional level here, there is the likelihood that this information might be somewhat fuzzy for no reason and full of inaccuracies. Faced with these informal masses of information that have the potential to undermine a patiently constructed image and deservedly won reputation, brands are confronted with the choice of continuing to keep quiet and losing their temper with whom they perceive to be busybodies. Or of taking the lead and accepting that only the word of a CEO, providing he’s a good ambassador and not too much of a pitchman, automatically makes people want to know more within a restricted perimeter.

The watchmaking industry is built on people made of flesh and blood. Empowering them and allowing them to quote occasionally could further cement the foundations of those who employ them. For what they have to say is worthy of any press release.

The rule and its exception

Having been tasked with providing copy for the JSH magazine (Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie) on the International Chronometry Conference organised by the SSC (Swiss Chronometry Society), I tried, with the agreement of its President, to obtain some information about one of the conference speakers. Naturally, I assured him that no information would be published before the day in question, at which time he was scheduled to speak in a lecture theatre in front of around 700 people, including rival brands and a few journalists. Just for the record, the speaker in question had already been asked to deliver his copy for ‘Actes’, the official event publication, a kind of scientific bible aimed at participants or those unable to attend. The entire conference content, including images and visuals, had therefore already been released by the company. Alas, the press department and upper management denied me access initially. Ultimately with the aid of logic and the President of the SSC, I was able to allay their fears by showing them that their in-house rules would not be undermined and that initial authorisation also covered this request. I was thus able to write my article.

The wisdom of transparency

The open source ethic is making its mark on an increasing number of watchmaking brands. Based on the premise that the customer is no fool, especially if we are talking about a collector or an enthusiast, and that anything can eventually be learned, they are taking the lead. Their press areas are accessible 24/7, without a password, and it is now possible for everyone to download high-res images, a privilege hitherto only reserved for the media or reps. And the names of their suppliers are clearly visible. It was, in fact, Maximilian Büsser who started the trend by adding "and friends" to his company name. MB&F instils the notion of a manufacturing collective. Genuine enthusiasts for its watchmaking pieces, those who want to find out all about their purchases, are delighted. This level of transparency cannot be viewed as giving information away, but strengthening it.

©

toute reproduction strictement interdite

Tweet

On the forum (in french)

Version française

English section