Watchmaking post

Stop, watch and learn!

Par Joël A. Grandjean /TàG Press +41

Classic makes a comeback. Watchmakers close their lids!

Suddenly, tastes have reverted to classicism. Have open-case watches been showing consumers just a little too much information? Whichever way you look at it, it’s time for the lids to come down, it’s all part of the natural cycle.

If our public transport system could guarantee the same independence, the same comfort level and a whole lot less worry than our own cars, we’d all take the bus or some futuristic spin-off. Garages everywhere would rid themselves of their snazzy do-it-alls, their operational vehicles, albethey monsters of technology. And their place would be taken by vintage beauties, customised models, “pimped” rides, design rarities, contraptions on wheels boasting all the latest cutting-edge technology.

The outmoded era of functionality

Well, that is what is happening on our wrists. Now that our environment is full of objects that tell us the time, even when we don’t want them to, now that this omnipresent time is constantly throwing itself in our face and, what is more, that it is ultra-accurate, our need for watches is changing. With quartz representing the peak of our expectations in terms of precision, our tastes and interests back in the 70s-80 migrated towards a mechanical style of watchmaking. Accurate, yes. But so much more alive. To those who have been observing the phenomenon from a distance, those who have not yet caught the bug, or been touched by the watchmaker’s grace, it is perhaps timely to recall and recapitulate that what we are talking about is not a simple return to the past. We are talking about a new form of expression made possible by the fact that, for functionality, time has run out.

Thus, since the beginning of the new era, one that brought about the incredible vibrancy of today’s mechanical watchmaking industry, there has been a tendency to simply open up the dial. Here one can admire a snippet of gear train, there a detail of the mechanism. I am not talking about the skeleton models that have existed since the dawn of time, which have their own distinct style. In this way, the legendary Sarcar brand has been joined by watch companies such as Pilo & Co, in its infancy, and others such as Frederique Constant. At the same time, and for those with more comfortable means, the open-case watch helped to re-establish such complications as the Tourbillon, whose key feature is that it adds a fascinating visual dimension to the wearing of a timepiece. The opening focused the gaze specifically on the regular rotation of the prestigious cage.

Dial exaggeration and denial

Gradually, the riveted or screw-down back, opaque and functional, was replaced by a crystal, usually a sapphire crystal. I remember a time in the 90s when the MHR watchmaking brand made a point of resisting the phenomenon in its communication campaigns. For the brand’s director, Marie-Dominique Pibouleau, there was no question of giving way to this emerging desire to show all, of stooping to the slightly dubious level of wanting to display the pedigree of one’s watchworks. But users had the last word. They longed to be able to gloat over the movement within their timepiece, appreciate the beauty of its regulating organs, be lost in wonderment at the sight of its pulsating works and mechanisms.

Gradually, the riveted or screw-down back, opaque and functional, was replaced by a crystal, usually a sapphire crystal. I remember a time in the 90s when the MHR watchmaking brand made a point of resisting the phenomenon in its communication campaigns. For the brand’s director, Marie-Dominique Pibouleau, there was no question of giving way to this emerging desire to show all, of stooping to the slightly dubious level of wanting to display the pedigree of one’s watchworks. But users had the last word. They longed to be able to gloat over the movement within their timepiece, appreciate the beauty of its regulating organs, be lost in wonderment at the sight of its pulsating works and mechanisms.

However, the outrageous good health of the mechanical watchmaking industry, until the recent crisis in 2008-2009, also permitted a number of excesses and wayward wanderings. Developing beyond the concept of a simple opening, the aperture on the dial spawned other ideas. It got bigger. The date window suddenly became disproportionately elongated, while the tourbillon window became fragmented. There then emerged a new breed of timekeepers intent upon dispensing with the dial altogether, and in some cases even transforming it into an overindulgence of technical details and useful information embedded in intricate gear train mechanisms. In a nutshell, the architecture of the movement, which, it must be said, is nothing short of stupendous, itself served as the dial. To use an analogy, it is a bit like a vintage car enthusiast refusing to close the lid, for fear of no-one being able to admire his magnificent pistons, or gleaming engine. Ever. Again.

In the workshop’s quest to go all out for effect, the shape of the watch also started to change. Watch designers then went to town: did we really need so many rounds, ovals, squares or rectangles? Using as a pretext their position at the top of the pyramid in the now well-trodden niche of (preferably high-mechanical) luxury goods, taking refuge behind the hypothetical expectations of a market weary of redundant classicism, new brands appeared and imposed a need for the total reworking of the timepiece. And all the while the economic euphoria ensued and the numbers of bottomless pockets belonging to new collectors swelled. The wrist was suddenly the arena for generations of high-tech, solid-state watches, sturdy, feather-light constructions with no hands or indexes, concept watches and talking pieces, sometimes in perfect working order. Watches that needed reams of instructions for us to fathom their new time-telling concept. Since we were paying a decent price, there was no point in mourning the loss of outdated functionalities! The nec plus ultra in this field was the Tourbillon launched by Yvan Arpa for Romain Jerome, which had not a single hand in sight. Spectacle for spectacle’s sake in the theatre of unnecessary exuberance.

References restored. Union Horlogère.

Weary of these excesses and exploratory wanderings, aside from a few brands, such as Urwerk and MB&F, who persisted in catering to the needs of a special group of enlightened amateurs, the industry is now reverting to classicism. Laurent Ferrier and H. Moser & Cie, and, before them, the functional aesthetics of François-Paul Journe’s Invenit et Fecit, helped to still the flights of watchmaking fancy and prompt a return to basics. According to this kind of style – Calvin is said to have admired it greatly – the height of good taste is the marriage of the complex and the beautiful concealed beneath a veneer of sobriety and discretion. Back in 1997, commissioned by the family watchmaking brand, Robergé, Alain Mouawad revived a Tourbillon model whose mechanism could only be observed through the back of the case. These brands thus walked in the footsteps of the world’s unshakable successes: Patek Philippe, the Rolex Oyster, the identity-strong Tank, the good old Altiplano, all of them references who managed to stand their ground through the toughest hours in the race for ostentation. Legends in their own time serving as waymarkers, simply holding their heads high above the sulking petulance of seasoned designers and uninhibited manufacturers.

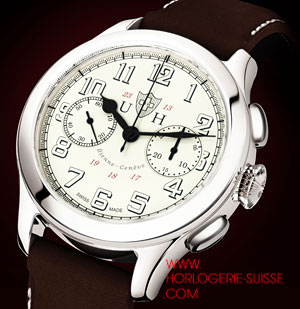

I have, myself, unearthed a little gem that has remained persistently unresponsive to the surrounding media pandemonium. Union Horlogère is a re-emerging historical brand, which has chosen to give free reign to its creativity in the field of traditional watchmaking according to today’s workshop rules and regulations. It might not wish me to unveil the 3D imagery instead of waiting for the photographs. In a true sign of the times, it, too, embodies an aversion to fashionable gimmicks.

BaselWorld has yet to confirm this cyclical return to classicism this year, but the trend is also marked by the re-emergence of ultra-flat movements complete with dials and bezels that would not say no to a (deliberately excluded) hand or two. Basic watchmaking has not yet uttered its last words. The trade of its founding fathers, the trade towards which everything always ends up gravitating, the trade whose motto is ‘always do better than necessary’, is the trade to which the consumer, after a few inevitably indigestible experiences in the development of this powerful virus, always returns… for good.©

toute reproduction strictement interdite

Tweet

On the forum (in french)

Version française

English section